A diagnosis of cancer is a scary and emotional time for any patient. With 1 in 2 Canadians diagnosed with cancer in their lifetime, researchers are seeking more effective, more targeted and less toxic treatments to help improve survival and decrease side-effects.

One of those researchers is Dr. Lillian Siu. Her résumé is impressive – Senior Medical Oncologist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Professor of Medicine at the University of Toronto, Director of the Phase I Program and Co-Director of the Bras and Family Drug Development Program at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, and holds the BMO Chair in Precision Genomics (2016-2026). She is also the Clinical Lead for the Tumor Immunotherapy Program at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre.

That is just the beginning. She has won multiple awards for research, but she is quick to point out that she is part of a team. Dr. Lillian Siu is one of many oncologists and research oncologists that are giving hope to Canadians and people around the world that there one day will be a future where cancer can be beaten. Learn more about her perspective on the future of cancer treatment and cancer treatment in general in our latest #WomenInspiringWomen.

Doctors and medical professionals are warning of a “Tsunami Of Cancer” post pandemic. How will our healthcare system deal with this?

We are dealing with a problem that we had not foreseen years ago. This pandemic has hit us hard and longer than we could have imagined. That means, that in the future, we have to anticipate what may come to us unexpectedly. That is the message in my view.

I think that in the short term, that we are all going to have to work hard and work together to overcome whatever comes after this pandemic, whether it is more cancer or other types of medical issues. The vision needs to be long term. For that reason, we need to invest in our infrastructure, in our people and in our research. I think that is the only way that we can build a strong enough healthcare system that can face any challenges that come to us and be able to manage them whether it’s a pandemic, new illness or a new issue.

With no end to the pandemic in sight, what can people that have delayed screenings do and what should they look out for?

We are still trying to do a lot of our care through virtual platforms. Some patients do need to be seen in person and we continue to do this under COVID precautions and restrictions. It’s not like the [Princess Margaret] Cancer Centre has shut down. Cancer is not an illness that you can stop testing and treating for a few years and take over afterwards.

If patients that are out in the community notice something of concern, they need to follow up with their family doctor or with their oncologist so that they can get in the queue to be seen and assessed. We have been working a lot of working overtime, weekends, etc. to catch up on the back log.

Explain the differences between chemotherapy, immunotherapy, hormone therapy and other targeted therapies.

Let’s take a step back. In terms of cancer treatment, there is obviously surgery which is cutting out the cancer. There is radiation that uses energy beams to treat cancer in a local or specific area. Then, there are drugs that include chemotherapy, immunotherapy, hormone therapy and other targeted therapies.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy are drugs that typically attack the cancer cells through some type of cell damage, usually by breaking their DNA so that the cells cannot divide or multiply. The challenge with chemotherapy is that normal cells have DNA as well. By breaking DNA which is present in those normal cells, we get normal cell tissue damage. The normal tissues recover, regrow and repopulate themselves whereas the cancer cells, at least for a period of time, will die and not repopulate or regrow.

Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapy is a type of treatment that has emerged in the last 10-20 years. We understand a lot more about the biology of what drives cancers and makes them grow and spread. There are a lot of what we call molecular pathways, or systems within the cancer cells that they use to grow and spread. What we are trying to do with targeted therapy is to develop drugs – pills or intravenous – that block or slow down these pathways. This is so that the cancer cells don’t have this kind of machinery to do what they want to do – which is to spread. Normal cells may or may not have these pathways. If they do, there will be some side effects as a result of blocking these pathways in the normal cells as well.

Targeted therapy tends to be more specific than chemotherapy. We are really trying to hone in on a very specific molecule that is only relevant to the cancer cells. That is what we call precision medicine because we know the Achilles heel and we try to attack the Achilles heel of the cancer.

Immunotherapy

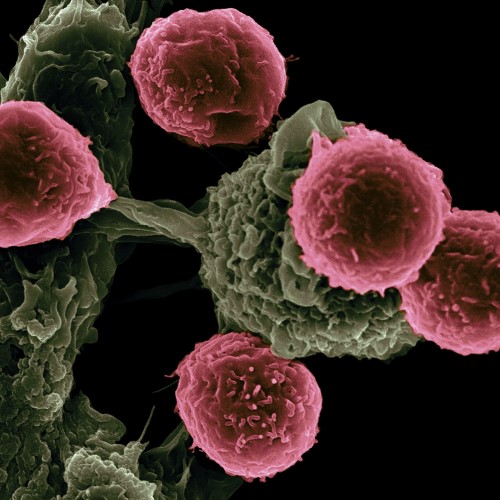

Immunotherapy is a completely different paradigm because we are no longer focusing on killing the cancer cells with drugs. We are trying to activate the patient’s own immune system to attack the cancer. Your body’s own natural defense is probably the best defense – there is a reason that it is there. The only reason that it hasn’t been working is because the cancer is smart enough to block that immune system from working. If we are able to remove that block, that would make the most sense in terms of fighting the cancer.

The most commonly used type of immunotherapy is called immune checkpoint inhibitors. Immune checkpoints are the “brakes” of the immune system that tumours frequently manipulate in order to shut down immune responses and protect themselves. These inhibitors remove the brakes so that cancer cells are now, once again, sensitive to being attacked by the immune cells.

Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy is very specific to certain cancers. Cancers like breast cancer and prostate cancer grow because they are stimulated by specific hormones – estrogens and androgens. Hormonal therapy typically blocks the secretion or manufacture of these hormones so that they don’t have that stimulus to grow. It is about using different ways to try to attack the cancer cells.

You had a huge breakthrough in immunotherapy research, discovering a way to predict which patients will benefit from immunotherapy. In layman’s terms, explain what this means for cancer patients?

The success is always the team’s success. The work comes from a large team at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and with many years of research from many scientists and investigators. We are all indebted to their time and effort.

The work that we have done is honing in on how we identify who will benefit from immunotherapy. As I mentioned, we want to activate the patient’s immune system to fight cancer cells, but that activation doesn’t work in all patients. Some patients respond very well and some don’t. In fact, they may respond adversely to the immunotherapy treatment. What we have been trying to do is look at different biomarkers to predict early on in the treatment who will be the responders and who will not.

The research that we have specifically looked at the circulating DNA in the blood. These are little pieces of DNA that are shed by the tumour. We want to see whether an early drop or disappearance of the tumour DNA in the blood predicts who will ultimately be the best respondent to immunotherapy. We were able to show that people who have a significant drop or clearance of this DNA in the blood are the ones that do the best on immunotherapy in the long term.

What types of cancer can be treated with immunotherapy?

Many types of cancer can be treated with immunotherapy. The cancers that are known to be the most responsive are melanoma (a type of skin cancer), lung cancers have high sensitivity to this type of treatment and kidney cancer. Then, there are cancers that are more intermediate in their response. We see response with 15-20% of the patients with cancers like head and neck and stomach cancer. There are cancers that do not respond at all to the current approved immunotherapy like pancreatic cancer and some muscle cancers.

There is a huge psychological impact on patients that receive a cancer diagnosis, particularly an initial diagnosis of metastatic cancer. How are cancer patients being supported emotionally at this time?

The pandemic has made it even tougher because the system is so stressed. Dealing with cancer at this time is particularly difficult for patients and their families. We see their distress and offer support through our psycho-social programs. They help patients deal with stress during the cancer journey. In-person support is obviously more difficult during these times, but virtual platforms make it possible for us to provide help.

We continue to see patients in-person or virtually. This includes physicians, nurses – support teams are always there. Sometimes, it’s not just the patient that needs support, but also the family, especially if they have young children. How do you break the news to your children, especially during the pandemic? You are home all of the time and if Mommy is sick – how do you handle this type of situation? We have experts that can provide access to psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers that can really be supportive with these types of issues.

A career in oncology has its fair share of highs and lows. How do you get through days when you have to deliver news that is devastating for patients to hear?

Oncologists are only human. I’m only human. Obviously, the days when you see responses and good results on your research or with your patients, it’s a great day. We are happy because ultimately, we are advancing the cure for a disease that is affecting so many of our families. On the days when there is bad news, it’s never easy, to be frank. Even after doing this for nearly 30 years, I still find it challenging to break that news. I try to ensure that patients understand that even when the cancer is not responding, they will continue to receive good support treatment. We learn from experience so that patients can benefit in the future.

I try to invest my energy, whether times are good or bad, into research. Ultimately, if you think about it, we have learned so much from the pandemic. We think that developing a vaccine takes ten years or more. With people working together, we were able to get the vaccine quickly. I truly believe that by investing in this kind of know-how, we can change the trajectory of how we manage diseases. The pandemic is a good example of when we work together, that power is there and there is nothing impossible if you put your will to it. When I have difficult times, this is where I think about how best to channel that energy. Instead of not working, I work harder to make things hopefully work better for future patients.

What is the future for cancer treatment?

I think that the future is bright. Ten years ago, when we had targeted therapy, we thought that we knew everything about the molecular makeup of cancer. We thought that we learned everything. Then, immunotherapy came along and opened up a whole new chapter.

Cancer is still, in many cases, an incurable disease but we are making progress. That kind of progress comes from the efforts of many and not just researchers. It’s people who support research such as our donors and our community. I truly believe that these kinds of efforts are worthwhile because we have had history prove to us that we are making progress decade by decade. Hopefully, this progress will come more quickly in the future.